Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) licensing in Bulgaria

The European Union’s Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 on Markets in Crypto-Assets (“MiCA“) became directly applicable on 30 December 2024. Bulgaria has now enacted its Law on the Markets in Crypto-Assets (the “Bulgarian MICAL“), giving the country full implementation of MiCA and triggering immediate obligations for crypto-asset issuers and service-providers.

EU regulatory background

MiCA introduces a single passportable licence for crypto-asset service providers (“CASPs”), imposing uniform conduct-of-business rules and prudential requirements, tiered by service class (the higher of EUR 50 000, EUR 125 000 or EUR 150 000 in paid-in capital or one quarter of the fixed overheads of the preceding year, reviewed annually). Article 143(3) of the MiCA allows Member States to reduce or waive the default 18-month grandfathering period (30 December 2024–1 July 2026) for entities that were already providing crypto-asset services under pre-existing national law.

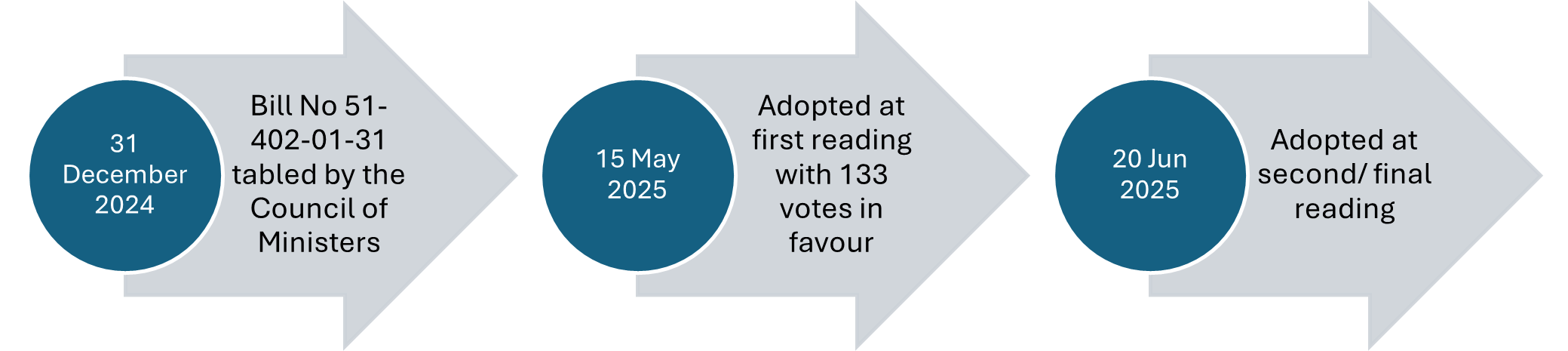

Implementation of MiCA in Bulgaria Bulgaria has opted for the full 18-month grandfathering period (until 1 July 2026), while attaching strict fit-and-proper and organisational tests to all applicants. Below is the legislative timeline for the enactment of the Bulgarian MICAL, pending its publication in the State Gazette:

Key features of the Bulgarian MICAL

- Token taxonomy clarified. The Bulgarian MICAL tracks MiCA’s three-pillar classification of crypto-assets: (i) asset-referenced tokens (“ARTs“), (ii) electronic money tokens (“EMTs“) and (iii) “other” crypto-assets.1 Distinct prudential and disclosure rules now attach to each pillar, ending years of doctrinal ambiguity in Bulgarian law.

- Supervisors. The Financial Supervision Commission (“FSC“) is the default competent authority for MiCA in Bulgaria. It licences and monitors asset-referenced-token issuers and CASPs.2 Where MiCA vests powers in the prudential supervisor of electronic-money tokens, those powers fall to the Bulgarian National Bank (“BNB“). The Bulgarian MICAL expressly carves EMT issuers out of the Act (save for market abuse rules in MiCA Title VI).3 EMT issuers must therefore be authorised under the Bulgarian Payment Services and Payment Systems Act (the “Bulgarian PSPSA“), for which the BNB is the licensing and supervisory body4. MiCA itself confirms that, as the EMT issuer is required to be an electronic money institution or a credit institution, the same prudential supervisor continues to be the competent authority for MiCA purposes5. The two regulators must cooperate: the FSC coordinates with ESMA and EBA6 and must notify the BNB when it applies certain enforcement measures to a credit-institution EMT issuer.7

- Licence timeline. The FSC must issue or refuse a CASP licence or an asset-referenced token licence within the terms envisaged under MiCA. The initial Bill envisaged that failure to reply would be deemed a refusal (“silent denial”). However, between first and second reading, the MPs scrapped the rule that the FSC inaction equals to silent denial. Commentators hail this as a “major predictability upgrade for investors”.8 The supervisor must now issue an express, reasoned decision within the timeframes envisaged under MiCA.9

- Transitional regime. Any virtual-asset service providers (“VASPs“) recorded in the National Revenue Agency AML register before 30 Dec 2024 may continue, without a licence, to carry out in the territory of the Republic of Bulgaria the activity for which they are registered until 1 July 2026 or until they obtain (or are refused) a MiCA licence, whichever is earlier.10 VASPs recorded in the National Revenue Agency AML register between 30 December 2024 and the date on which the Bulgarian MICAL enters into force are required to file an application for a MiCA licence within three months of that entry into force. Within thesame period, those persons are required to bring their activities into compliance with the MiCA and the Bulgarian MICAL.11

- Sanctions. Sanctions are envisaged in the MiCA itself and implemented in the Bulgarian MICAL. Administrative fines may reach the higher of BGN 5 million or 6.25 % of global annual turnover for a first offence and up to the higher of BGN 10 million or 12.5 % for a repeat breach. For certain specified breaches, the fine may be the higher of BGN 15 million or 7.5 % of global annual turnover for a first offence and up to the higher of BGN 30 million or 15 % for a repeat breach.12 In addition, the FSC is empowered to:

-order an immediate suspension of a crypto-asset service for up to 30 working days or impose a permanent ban;13

-halt or prohibit a public offer or the trading of certain crypto-assets on a platform;14

-compel issuers or CASPs to amend or withdraw white-papers and marketing materials that are incomplete or misleading;15

-dismiss individual board members or senior managers responsible for violations;16

-publish every enforcement measure and penalty on its website, thereby “naming and shaming” non-compliant firms.17

The FSC is authorised, “when no other effective means exist to halt the breach” of MiCA, to instruct any third party (e.g. hosting company, domain registrar, content-delivery network) to: (i) remove specific content; (ii) restrict access to an “online interface”18 (the website or app through which a CASP serves EU clients); or (iii) display an explicit warning to users landing on that interface. This measure is conditional on a risk of “serious harm to the interests of clients or crypto-asset holders” and may be complemented by a court-ordered injunction19. Opponents argue that these powers grant the FSC an Internet “kill switch’ and constitute a form of censure. Supporters, however, counter that the clause simply transposes Art.94(1)(aa) of MiCA, which gives national authorities identical powers to act against rogue cross-border operators. With the Bulgarian MICAL in force, Bulgaria shifts from draft proposals to a fully operational MiCA regime. Pre-registered VASPs have a narrow, domestic-only runway until 1 July 2026; all newcomers must prepare complete MiCA files and apply for a MiCA licence. The steep, turnover-based fines underscore the need for rigorous compliance from day one.

Download the Client Alert here

- Art. 5 of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 3(1) of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 1(2) of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- To this effect, new Chapters 10a and 10b are introduced in the Bulgarian PSPSA with the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 48(1) of the MiCA. ↩︎

- Art. 3(2) of the Bulgarian MICAL and art. 96 of the MiCA. ↩︎

- Art. 22(1) of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- https://forbesbulgaria.com/2025/06/20/okonchatelno-balgariya-ima-zakon-za-targoviyata-s-kriptoaktivi/ ↩︎

- Arts 6(2) and 15(5) of the Bulgarian MICAL. Under Art. 63(9) of the MiCA, competent authorities are required, within 40 working days from the date of receipt of a complete application, to assess whether the applicant crypto-asset service provider complies with the Act and to adopt a fully reasoned decision granting or refusing an authorisation as a CASP. Competent authorities are required to notify the applicant of their decision within five working days of the date of that decision. That assessment takes into account the nature, scale and complexity of the crypto-asset services that the applicant CASP intends to provide. ↩︎

- § 3(1) of the Transitional and Final Provisions of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- § 3(2) of the Transitional and Final Provisions of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Arts 37(3) and 38(3) of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 28(1), p.1-3, 5 of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 28(1), p.10-13 of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 28(1), p.7-9, 15 of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 28(1), p.19 of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 46(1) of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Art. 28(1), p. 27 of the Bulgarian MICAL. Definition of “online interface” is contained in § 1, item 9 (mirroring MiCA Art. 3(1)(38)) of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎

- Under Art. 36 of the Bulgarian MICAL. ↩︎